I hope so too. Thank you for posting the link about the Copenhagen study. I think they have different outcomes of interest and the microplastics angles is interesting and in my opinion an area of research that needs much more attention. Nutritional epidemiology is so complicated. I had to chuckle a little when they were describing in the methodology section that subjects were blinded as to whether they were receiving the unprocessed and ultraprocessed diets. I can tell you from experience that I can usually tell the difference between a floret of raw broccoli and a package of Oreos.

GIGO.

Don’t eat that shit. It screws up the insulin/glucose metabolism and makes you more insulin resistant.

This is how you create people who can’t go more than 4 hours between snacks, and who feel like “I am dying” if they go more than 8 or (gawd ferbid) 12 waking hours without eating.

I do make all of our sausages… but I don’t dip my own nuts in chocolate. I fear the wife wouldn’t approve.

(post deleted by author)

You won’t know for sure until you try ![]()

Wow, this is super interesting. Thank you for participating. I would get cranky fast on the UPF phase of the diet, so I hope that part isn’t too hard on you.

Maybe she’d waaay approve. Love to make my own sausages, but my lazy bone says that my friends always make great stuff for me, so why start and ruin the bonding time? There are some terrible sausages out there, and they taste way over processed, probably in an effort to make bad meat taste good.

I like my nuts raw.

Laura Thomas, author of the Can I Have Another Snack? Substack, has been tackling UPFs for a while and interrogating presumed certainties about them. She’s also unfavorably reviewed Ultra Processed People.

Worth checking out: https://www.canihaveanothersnack.com/tag/ultra-processed-food/?ref=can-i-have-another-snack-newsletter

What blows my mind is that canned beans are considered UPFs.

I read Laura Thomas’ review of UPP until I hit a paywall. In any case she has a point about the style of writing and lacking complexity but my take is she’s looking at the trees but not seeing the forest or big picture. The big picture, imo, is industrial food systems run by large corporations are a big issue and UPP is sort of a pop culture clarion call meant to wake people up.

I get looking at the details, complexity and giving a critique is part of the scientific process, so she is doing everyone a favor in the long run. However a lot of people, including me, really weren’t aware of the scale and magnitude of ultra processed food. On that note, that’s why it was a best seller and I think the style of writing is appropriate. Generally speaking the author of UPP was breaking down the big blocks of science for general consumption and sending a warning. Good science? Perhaps not but still a service to people who eat food.

Yes, ultra processed food is complex and breaking it down in detail is needed. But the pop culture wake up call is also needed. Yes there are gray areas and a lot of unknowns, even benefits to ultra processed food (baby formula) but the profit motive and large corporate backing gives motive and a simple understanding. Those corporations aren’t making ultra processed food for our health or well being. Laura Thomas is doing the science and everyone a favor but UPP is really more about calling out a big problem and asking WTF.

I don’t think all canned beans are considered UPF but it really depends on the brand (and obviously what they add to the beans) . There brand which are pretty much beans and salt and wouldn’t be considered UPF. But other brands add preservatives or EDTA to preserve color or you have nitrates in baked beans when we are in UPF territory

I was thinking the (commercial?) canning process was part of what put it in that catagory .

Canning doesn’t make a food UPF but the ingredients used

There are so many warnings about getting political on HO but apparently people are down with anti-fat bias. I won’t comment further save to say I like you lot but these attitudes are super disappointing.

Her email says it’s free to read, so here it is un-truncated:

![]()

Can I Have Another Snack?

Book Report: Ultra Processed People

By Laura Thomas • 14 Jan 2025

View in browser

Hey team and welcome to Can I Have Another Snack?, a newsletter where I’m sacrificing myself for the greater good.

This essay is free to read; please consider sending it to a few friends who might enjoy it, and encourage them to subscribe.

If you like what we do here and want to support our work, why not consider becoming a member of the Snack Pack - it’s £5 per month or £50 per year and you get access to the entire CIHAS universe: weekly discussion threads, bonus podcasts, my monthly advice column Dear Laura and our new Discord channel. To help you make up your mind, this January we’re offering a month’s free trial when you sign up to a paid subscription - giving you access to a free full calendar month of CIHAS content . Why not check it out here.

Thanks for being here!

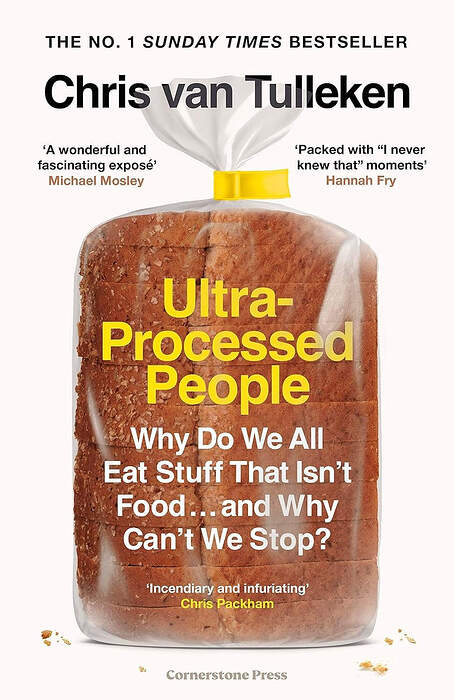

I went into reading Ultra Processed People with an open mind. I’d heard from colleagues and friends that author Chris van Tulleken had done a pretty good job of de-centring a personal responsibility narrative. His emphasis was on encouraging people to think about the influence of the food industry in shaping our eating habits; the so-called ‘commercial determinants of health’. The thesis of the book is that commercial interests have paved the way for a food system that is overly reliant on concoctions of synthetic chemicals like flavourings, colourings and emulsifiers that are reconstituted into cheap ‘food-like substances’ rather than ‘real’ food. These fake foods and the chemicals contained therein are hazardous to our health.

To frame his argument, van Tulleken uses the NOVA classification, which ranks foods into four discrete categories: unprocessed or minimally processed foods like milk; processed culinary ingredients like salt and honey; processed foods like cheese or sourdough bread; and finally ultra processed foods (UPF) like supermarket bread and breakfast cereals. UPF, van Tulleken posits, harms our bodies directly, by ‘increasing rates of cancer, metabolic disease and mental illness’. But it also causes human suffering through ‘displacing food cultures, and driving inequality, poverty and early death’, as well as through environmental damage. He vignettes his breakdown of the science with personal anecdotes of ‘experimenting’ on his own body; first with a UPF-free diet, followed by a diet high in UPF.

And certainly, his narrative is compelling. He is a good storyteller. He writes with conviction. At several points I had to consult with the Nutrition Group Chat, and various smart friends received a text amounting to ‘am I losing my mind or…?’. This confident storytelling is probably why Ultra Processed People (UPP) has been such a runaway success; A Sunday Times bestseller; winner of the Fortnum and Mason’s Debut Food Book of the Year in 2024; translated into (as far as I could tell) Romanian, Dutch, German, Norwegian, Portuguese, Czech, Swedish, Italian, Spanish, Slovakian, Bulgarian, Finnish, Turkish, and French. It has also enjoyed a hardback and paperback release in the UK, Canada, and the US. The UK edition alone has sold almost 320,000 copies according to Nielsen Bookscan (December 2024) and that is excluding audio and e-book sales. That represents almost £3.5 million in sales, just for the UK release of the physical book.

The Offending Item

And while the assuredness in the writing and storytelling makes for a convincing read, it is also the book’s undoing. Over and over again, van Tulleken writes in absolutes, using causative language and leaving little space for doubt and uncertainty. This belies the ambiguity and unknowns that undergird our understanding of the research around UPF. We should be wary – and in fact reading UPP made me weary – of binaries. ‘Certainty is a dead space’ writes author Katherine May in Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times, ‘in which there’s no more room to grow’. Compelling writing is not the same thing as good writing. Just as compelling science isn’t automatically synonymous with good science.

May continues that ‘wavering is painful’. Indeed. Van Tulleken seems deeply reluctant to sit in the discomfort of not knowing. And while there may be a broad consensus that UPF is a signal in the noise of contributors to ill-health, as of yet, we don’t know exactly how loud the signal is, nor can we fully decipher it.

Certainty bulldozes complexity. Research published in May 2024 by Harvard University highlights some of the contradictions. They found that eating sugar sweetened breakfast cereal, processed meat, and sugar or artificially sweetened drinks carried a risk of premature death. Foods like unsweetened breakfast cereals and wholegrain bread, although considered UPF, did not carry the same increased risk. What’s more, the overall increased risk (or effect size) was small. The researchers concluded what any nutritionist or dietitian would tell you: overall diet quality is what matters the most. Van Tulleken speaks with such assured authority so as to leave no space for caveat or nuance.

![]()

Does Ultra Processed People also make you want to scream? Come share your thoughts over on the CIHAS Discord channel

With the research that van Tulleken cites in the book, he is selective in how he reports the data, glossing over the parts that don’t fit neatly with his definitive narrative. For instance, in the section where he describes the work of researcher Kevin Hall, I have written in the margin ‘a deliberate misrepresentation of this study’. I’ve written in-depth about how Hall’s work is frequently weaponised to drive a specific narrative. But the study itself is full of tensions, discrepancies, and unanswered questions. In some cases it makes the opposite case that UPF critics often cite. For instance, the researchers didn’t find evidence that UPF is hyperpalatable or that there was elevated blood glucose levels in the groups eating more UPF. It also found weight gain began to stabilise relatively quickly after beginning the UPF diet. This raises something troubling: either van Tulleken wasn’t reading the study very carefully, or, I was right about the deliberate misleading. Either way isn’t great. I’m also troubled by how van Tulleken is comfortable citing animal and in vitro research when it furthers his argument; criticising the same methodology when it refutes it.

I don’t want to get too caught up in the specifics of any one study though because I think it detracts from the global point: presenting the research on UPF in absolute terms distorts the tensions, ambiguities, contradictions and unresolved questions surrounding UPF; it is far from a settled matter.

In the chapter added to the paperback edition of UPP, van Tulleken responds to virtually all attempts from the scientific community to interject some balance, by closing off their arguments, often in ways that themselves distort the true picture of things. Anyone who has taken money from industry is automatically a shill, even if they have an otherwise unimpeachable academic record. Hell, even if they are one of the foremost scholars in nutritional sciences, having had any dealings with the food industry immediately discredits them in van Tulleken’s view. Despite this, there is no mention that nutritional science is, like most life sciences, obscenely underfunded. In our academic environment of publish or perish, not many researchers have the BBC and Guardian connections – ones which have undoubtedly buoyed the sales of his book – that look favourable on grant applications; not many researchers are given the opportunity to make documentaries based on their personal anecdotes to secure grants, something that van Tulleken openly admits he’s doing in the book.

I am not claiming there aren’t issues with conflicts of interest in nutritional sciences – patently there are. But there are also double standards in what constitutes a conflict of interest. Another choice example is where van Tulleken disparages the opinion of a dietitian who quite sensibly cautioned against tarring all UPF with the same brush. He asserts her opinion was obsolete because she had not published a peer-reviewed paper on UPF. There is something jarring here about a male doctor – who as it stands has himself not published any peer-reviewed scientific evidence on UPFs* – deriding a female dietitian, who is presumably much more experienced in counselling diet-related behaviour change than he is. Moreover, it suggests van Tulleken is feeling backed into a corner, no longer engaging with the substance of an argument, and instead resorting to ad hominem and ‘poison-the-well’ attacks to discredit and undermine professional opinion.

As regular readers will know, I have written fairly exhaustively about UPF; I am no longer interested in engaging in debates about whether UPF is ‘good’ or ‘bad’. What I am interested in is that despite denying he is furthering a narrative of personal responsibility, van Tulleken’s arguments are constructed in such a way that does exactly that.

Disgust – whether an intentional literary device or not – is woven throughout the text. Van Tulleken frequently evokes revolting imagery to drive home how abhorrent UPF is. On at least two occasions he uses the word ‘exudate’ to describe the origins of ingredients used in UPF manufacturing. Exudate is, according to the MedLine Plus medical encyclopedia: 'fluid that leaks out of blood vessels into nearby tissues. The fluid is made of cells, proteins, and solid materials. Exudate may ooze from cuts or from areas of infection or inflammation.’ To you and I, exudate is pus. This description is clearly intended to elicit a disgust response. But by this definition, arguably many valuable nutrients would – like the molecule he’s describing – be considered bacterial ‘exudate’, such as vitamins B12 and K, as well as butyric acid: a well-documented and potent anti-inflammatory made by gut bacteria.

Another way that van Tulleken repeatedly evokes disgust is through the frequent listing of ingredients that are used in UPFs alongside inedible, non-food products. For instance, when discussing the emulsifier polyoxyethylene sorbitan monooleate he lists: ‘kosher pickles, ice cream, aerosols of whipping cream, toothpaste, moisturising cream, shampoo and hair dye’. It’s not hard to find examples of ingredients common to both food and non-food substances; there is water in my shampoo and conditioner, there is vitamin A in my skincare. And while the argument evidently hangs on the appeal to nature fallacy, it is also besides the point. By evoking strong feelings of repugnance in the reader, van Tulleken is effectively linking UPF with notions of morality. Disgusting food contaminates and taints the eater, rendering them morally impure for eating it. We therefore have a moral imperative as individuals to avoid them.

By tying UPF food to morality, there is the obvious reinforcement of unhelpful ‘good’ food/ ‘bad’ food binaries. But the more troubling effect is that food continues to eclipse the broader social and structural determinants of health. Yes, van Tulleken speaks to the inflated influence of the food industry on shaping food policy and nutrition research. Yes, he talks to aggressive marketing techniques and an insatiable thirst for profit that is built on an economic of extraction and exploitation. But this is not unique to the food industry; virtually every modern enterprise requires exponential growth to succeed. Van Tulleken has seemingly just discovered the fundamental drivers of capitalism and he is shooketh.

Photo by Franki Chamaki / Unsplash

Now don’t get me wrong, I have exactly zero sympathy for the food industry. In many ways I agree with his arguments and I want nutritious food to be accessible to everyone. But where we diverge is here: he is using the food industry to scapegoat more insidious inequity. Throughout the book there are plentiful references to how health has deteriorated since the 1980s. Van Tulleken’s view is that there is a direct link between increased UPF consumption in this period and concomitant increases in body weight (I’ll return to weight shortly). But by foregrounding changes in the food supply, van Tulleken occludes the transition, first to neoliberalism and then advanced liberalism, that has defined the past 50 years. In this same period, we have seen a desecration of any kind of social welfare system, a systematic dismantling and privatisation of the NHS, and 14 years of Tory austerity. Innumerable lives have been lost and disabled by hostile policies. Yet van Tulleken puts the proverbial UPF cart before the horse; recall that he states that UPFs are an antecedent to poverty. So prove it.

Van Tulleken is not ignorant to these issues; he makes frequent, if fleeting (and condescending), references to poverty. But rather than addressing root causes of structural inequality, he doubles down on spotlighting UPF as the ‘real’ issue by offering a couple of trite policy suggestions; warning labels on food packets and taxation. I won’t discuss taxation here – as Karen Throsby has used the sugar tax as a lens to discuss how these taxes are designed so as they cannot ‘lose’.

But the logic that front of package labels offer consumers ‘choice’ is worth interrogating. This sentiment is prolific in public health nutrition discourse; when presented with all the information, it’s easy to make the ‘right choice’. In Mother State: A Political History of Motherhood, writer and academic Helen Charman asks ‘under what conditions is choice possible, anyway?’. She is discussing ‘choice’ as it relates to reproductive justice: ‘But even in a country where abortion is – within limits – legal, it is only a matter of choice if both options – having a baby and accessing a termination – are equally materially possible’. I do not wish to compare the decision to terminate a pregnancy with a trip to the supermarket; these are plainly in different spheres. But I do think that abortion and reproductive justice are helpful lenses through which to interrogate the logic of choice. As with the decision to keep or terminate a pregnancy, the ‘choice’ to eschew UPF is largely determined by the material conditions of our lives. A hostile state, economic precarity, and inequity drawn down class and racialised lines are just some of the factors that affect those material qualities that Charman cites as disruptors of equally weighted ‘choice’. Similarly, van Tulleken, who has just welcomed his third child and – I’m going to go out on a limb here – doesn’t have to contend with a 2-child benefits cap to feed that child, has considerably more ‘choice’ than the average consumer. ‘Choice’, as Charman pointedly puts it, ‘is not a neutral demand’.

Van Tulleken writes that ‘we know that low-income households tend to eat more UPF for many often-sensible reasons’. Emphasis mine. ‘Sensible’ reasons, he asserts, are things like affordability, convenience, shelf-stability, and that children are usually happy to eat it. It leaves us wondering what constitutes an nonsensical reason to eat food? Joy? Pleasure? Fun? Care? Clearly that would just be foolish.

Choice is not neutral or equal when some choices are judged to be feckless and ‘irresponsible’. This is also revealing insofar as it shows a phenomenally narrow understanding of why people eat the way they do; eating, in van Tulleken’s view, is understood almost exclusively as a biomedical act, divorced from any sociality, pleasure, or acts of care.

By the end of the book, I am left sitting with the question of why van Tulleken is so content to wholesale blame the food industry when there is so much else to consider? It is too easy. Too binary. Too unquestioning. I think – as is so often the case lately – French theorist Michel Foucault has some insight (all roads lead to Foucault, it would seem). His concept of power/knowledge asserts that knowledge – in this case in the guise of scientific expertise – is intimately linked to power. Science does not simply produce disinterested, empirical knowledge, but is also a source of power. His status as ‘expert’ confers authority that shapes how the political and ruling classes view food, bodies, what is tasteful, and what is disgusting. We only need to look at the MAHA contingency to see how this rhetoric gets co-opted by the right and far-right.

Van Tulleken’s unimaginative policy suggestions deliberately do little to challenge the status quo. Instead they are the means through which authoritative voices in any given ‘policy community’ leverage power over those whose behaviours are deemed to need ‘correcting’. Van Tulleken’s suggestions are unthreatening to the institutions that he is so beloved by, and which, in return, confer him with so much social and political capital. In order to have meaningful choice – not just the illusion of it – we would need much deeper, radical action: the sort of changes that Black female scholars like Angela Davis have been demanding for decades. It would require an uncomfortable analysis of power, not slack fingerpointing at the food industry. It would mean taking care work, food work, and women’s work seriously. It would mean prioritizing not just ‘adequate’ but comfortable housing, tackling fuel poverty, and dismantling benefits caps. It would mean equal access to free school meals, not just for those in the capital.

Get a month’s free trial to paid content this January!

Returning to the subject of weight; towards the beginning of the book, van Tulleken makes a ham-fisted attempt at addressing anti-fat bias (which he sanitises to the more palatable ‘weight-stigma’). He – after consulting with a single fat ‘friend’ who was the subject of one of his documentaries – lands on the contested ‘person-first’ language to describe fat bodies: ‘person with obesity’. He states that the word ‘obesity’ is – and I quote – ‘offensive’. This is revealing insofar as it shows no attempt to even try to understand the material implications of living in a world that is so deeply dehumanising and violent to fat folks. ‘Offence’ does not kill people. Anti-fatness, does. Make no mistake: van Tulleken does not stand in solidarity with fat folks.

This is evident in how adeptly he has woven disgust with fatness. As we have established, the thread of UPF as revolting ‘non-food’ runs throughout the book. Simultaneously he makes the claim, in several different ways, at several different points in the book, that UPF is causative of ‘obesity’. Aside from the fact that this flattens the complex determinants of body weight, it ties fatness with something he considers gross. Now, van Tulleken is smarter than saying ‘you are what you eat’, but the subtext is there nonetheless.

And while van Tulleken narrows in on fatness, I believe it is a stand-in; shorthand for anyone who is deemed ‘dirty’, ‘contaminated’, or otherwise ‘impure’ - be it migrants, disabled folks, trans people, or benefits claimants. It is a way of imposing a social hierarchy and distinguishing oneself from the ‘repulsive’ other. The person we imagine eats UPF; the person we are disgusted by. This is something I wrote about here, and will again quote Baker and Walsh’s writing on purity, defilement, and the idealisation of food:

‘Cleanness and uncleanness serve as symbolic functions to maintain society’s boundaries; disgust felt towards those who transgress social boundaries. Purity is, thus, best understood as the achievement of an ordered system, collectively classifying acceptable foods to consume, while also rejecting others as pollutants; as a signifier, purity speaks to the collective through its relationship with the defiled, rather than simply being an inherent property or condition of a phenomenon’.

Throughout Ultra-Processed People, the problem is framed as one of ignorance - of ‘not knowing’ as Karen Thosby put it - and the solution as one of education and warnings. Where does this leave us if we do not or cannot act on such information? What do we risk by reducing our food choices down to being a by-product of a nefarious food environment? Why should our food policy be dictated by people who will never be impacted by it? And lastly, what do we say about what and who we value when we prioritise future-oriented ‘health outcomes’ and imagined costs to the NHS over immediate needs and care?

Fundamentally, the NOVA classification is an epidemiological tool; it doesn’t change the advice about what to eat most of (whole grains, legumes, fruit and veg, nuts and seeds, meat, veg and dairy/alternatives). But by tying it to disgust and making it a moral imperative not to eat certain foods, van Tulleken shifts it from an epidemiological tool to a personal project.

*I found a study protocol on Pubmed with his name on it but the study findings have not yet been reported or passed peer review as far as I can tell

Any updates on your studies ?

I thought this discussion here in this thread is quite fair and balanced, not sure where you see problems

This is how I see it. Big Agra vs. Big Pharma, like two giant Godzilla’s duking it out. Tiny humans are better off out of the way before they get stomped on.

Isn’t that bit much conspiracy theory ?

You guys have a point. Big Ags aka industrial food creates health issues and they don’t see it as their problem, just collateral damage. People have free choice even if trillions are spend on marketing., engineering more addictive foods and suspect industry backed studies promoting certain angles to secure profits. Big Pharma is happy to solve problems they didn’t create as long as it’s profitable and makes shareholders happy. Making a profit and success is human nature and nothing wrong with that…up to a point, like when they game the system or create messes like Oxycontin. In any case, Big Ag and Big Pharma create a feedback and profit loop, leveraging negatives. They are simpatico in a dysfunctional system. The sensible thing to do is eliminate the negatives but there’s less profit, more work. Animals, humans and corporations like low hanging fruit.

Can I Have Another Snack?•Laura Thomas

Can I Have Another Snack?•Laura Thomas